a deep(ish) dive into mayoral candidate's plan for city-owned grocery stores

plus bird flu, tariffs threatening our trash cans of tomorrow, Gowanus gets a grain mill & spicebush winter jam

Photo by Kara McCurdy, via the Mamdani campaign.

Welcome to The Knife Bloc!

NYC’s most erratic newsletter on local politics, food, and labor is back! (Hopefully with more regularity in 2025.) Since I last published, I started working on two new NYC-based Substack newsletters, DOUGH, by mail, and Close Friends (written by my dear friend Erica Marrison). If you’re interested in thoughtful reflections on popular culture in 2025, check out Close Friends, or gaining a deeper understanding of economics and personal finance (but conveyed in the vernacular/design language of a liberal arts grad) then DOUGH is your girl. Physical editions coming soon to a coffee shop near you.

I also launched my own new project, screen time, which is a weekly(ish) guide to the film screenings, retrospectives and new releases premiering in NYC — the goal being to get us all out of our apartments to the movies. Even though it is definitely, unapologetically, NYC-focused, I still think it could be a cool read if you live elsewhere? Give it a try and let me know, pls. Film is a community medium; and we’re gonna need community in 2025.

But now, a new year is underway, bringing with it the promises of somehow. yet another. election. Yes, 2025, too, is an election year if you live in NYC. I know. We’ll get through it together, I promise. In November, New Yorkers will choose a new mayor, and campaigns are already underway. Read on for more on how this election intersects with food justice and affordability.

With that, I hope you enjoy this edition of TKB!

TL;DR

Inside a Rikers Island Kitchen, Dull Knives and Critical Jobs.

Automation in Retail is Even Worse Than You Thought. TL;DR: at least up until October 2024, Kroger was exploring a partnership with Microsoft to use facial-recognition technology to identify individual customers and provide them with a unique price.

Migrant vendors park carts as their American dreams slip away.

As baristas at a Park Slope Starbucks strike, the NYPD responds with arrests, Hell Gate reports.

Long Island farm forced to kill entire flock of 100,000 ducks amid bird flu outbreak.

Near the end of 2024, New York State delivered $6.5 billion in additional food assistance to low-income and working New Yorkers. It was distributed through a number of emergency food providers (including the one I operate in my day job, full disclosure) with existing partnerships with the city. We received ours through HPNAP and Nourish grants (both of which state-funded and are administered by United Way, and together make up about 20% of our funding). HPNAP focuses on supplying fresh produce to food pantries and soup kitchens and Nourish provides funding for emergency food providers to purchase from NYS suppliers (such as seasonal produce, local meat and seafood, and even value-add products like yogurt and grains). In case it is not clear, I’m unironically a fan of both programs — and even if I’m no fan of Kathy Hochul’s, this was a nice surprise.

Brooklyn Granary & Mill brings a gristmill to Gowanus. Written by TKB editor Michaela Keil!!!

And finally — Trump’s tariffs (which seem yet to materialize? Will 25% tariffs be the “Infrastructure Week” of his second term?) threaten rollout of NYC’s $1000 trash can of tomorrow.

Photo by Kara McCurdy, via the Mamdani campaign.

mayoral candidate wants to open a “city-owned” grocery store in every borough

Grocery shopping in NYC requires the skill, endurance, and dedication of an Olympic sport — especially if you’re trying to save money and avoid extortion. You have the greenmarket for luxuries, Trader Joe’s for affordable snacks, cheese, frozen meals, and decent produce, the international market for bulk spices and a deal on decent olive oil, the guy on the corner for fruit (paid for in cash), and your local bodega in a pinch. All your goods will then need to be hauled in a tote on the subway, in the basket of a Citi Bike, or, for the more sophisticated among us, in a so-called “granny” cart. Still, even after all this schlepping, you’d be hard-pressed to describe any of these options as a surefire source for a “great deal.”

But a NYC mayoral candidate has an ambitious proposal to create a one-stop-shop source for affordable groceries, hopefully closer to home. Back in late October, Ugandan-born Zohran Kwame Mamdani entered the 2025 NYC mayoral race with the temerity, enthusiasm, and graphic design language of a cheery summer boardwalk. In the final weeks of 2024, he grabbed headlines for running the New York City marathon and for his straightforwardly progressive, easy-to-articulate policies (Free buses! Rent freeze! Nordic-inspired baby boxes!). One of the many proposals likely to be of interest to TKB readers? City-owned grocery stores.

Like most things, there’s no single straightforward explanation for why food prices are so high in some neighborhoods and why good deals are few and far between. One of the most well-documented theories is that there are just fewer grocery stores, period. Both here in NYC and around the country. Fewer and more disparate grocery options drive up costs and decrease accessibility, forcing New Yorkers to chase savings from one end of the city to the other. Or, to sacrifice cost-saving for convenience and do a lot of their shopping at their more expensive local bodega.

But that is only part of the story. Food policy enthusiasts first coined the phrase “food desert” in 1995 (I prefer “food apartheid,” here’s why), which is the crisis of many Black, Brown and Indigenous communities (in NYC and beyond) not having affordably-priced grocery stores nearby, limiting access to quality fresh produce in these communities, which is linked adverse health outcomes. On its face, Mamdani’s proposal could address this. If the five proposed city-owned stores were strategically located in their respective boroughs they could provide some of these communities with the grocery store they need.

Unfortunately, it probably isn’t that simple.

If the problem is fewer grocery stores, it makes sense then the solution would be, as Mamdani proposes, to open new ones. But municipalities have been trying this for three decades and seen only limited success on both fronts: actually eliminating food deserts and getting stores open in the first place.

In 2011, in the depths of the financial crisis, the Obama administration announced a plan to combat food apartheid with the Healthy Food Financing Initiative. Every year since then, Congress has continued to allocate an average of $28 billion across three federal agencies to close the “grocery gap,” according to ProPublica.

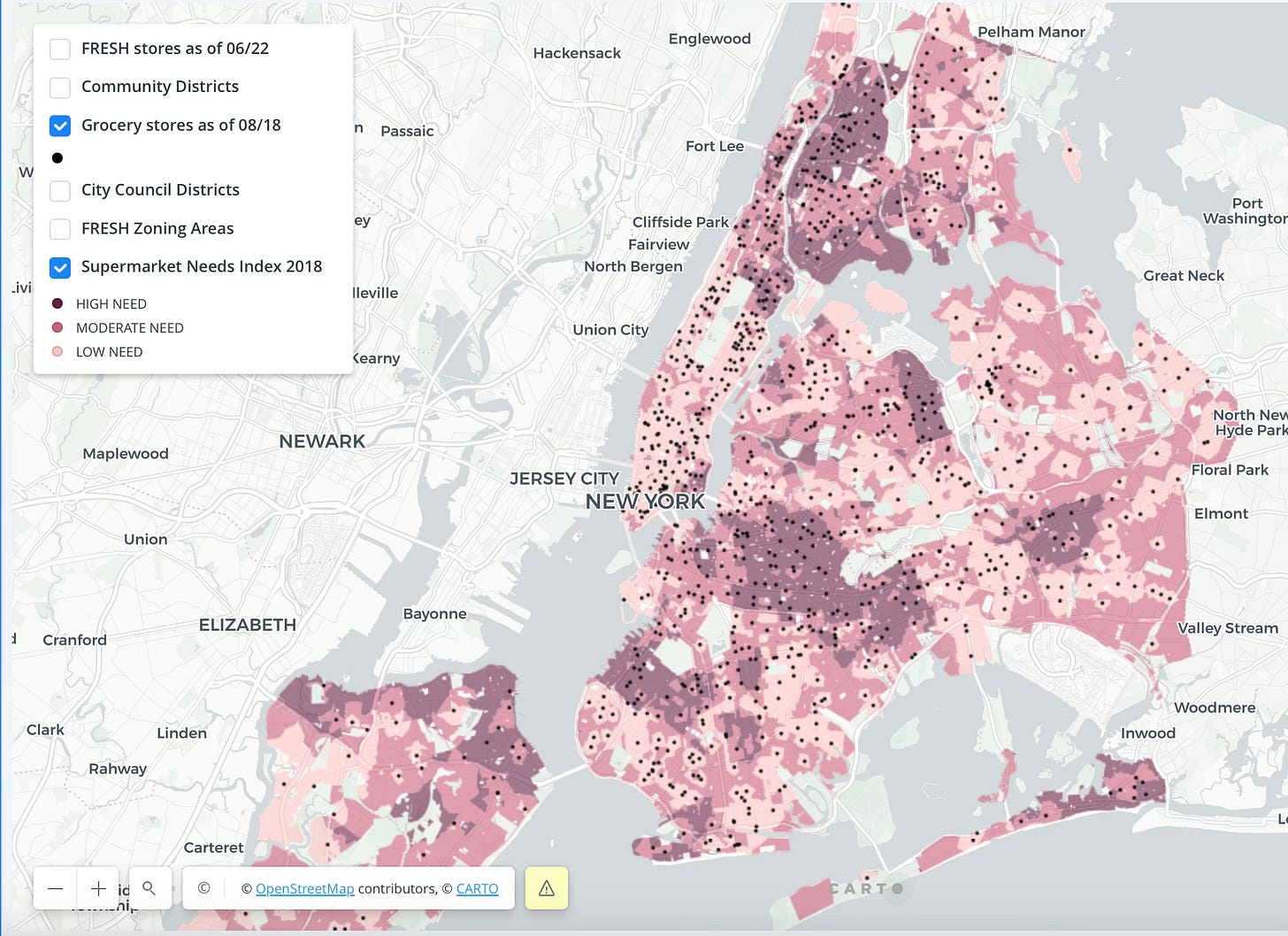

In 2009, NYC lawmakers launched the Food Retail Expansion Support Health (FRESH) program, which uses subsidies and tax leniency to coax grocery stores to set up shop in neighborhoods classified as being in “high" need of a grocery store (which is based on a couple of factors including population density and supermarket square footage). In 2021, when the program was expanded, FRESH boasted 30 new stores benefiting from the program, which put a grocery store within walking distance of a total of 1.2 million New Yorkers. In that time, parts of the Bronx and Brooklyn have been reclassified from “high need” to “moderate.”

Via NYC Planning and NYC Department of Health, 2008.

Via NYC Planning, 2018.

This is promising, but considering these openings average out to less than two new grocery stores per year, and less than three percent of the total estimated grocery stores in the city, I think it’s safe to say this program falls short of a resounding success. (It’s also worth noting that while there’s been improvement in some areas, it appears food apartheid has intensified in other areas in that time, such as the North Shore in Staten Island and in parts of eastern Queens.) Further, while it’s difficult to measure if the number of people living under food apartheid has been meaningfully altered since FRESH went into effect, we do know the number of folks impacted by food insecurity in NYC has stubbornly hovered between 1.2 and 1.4 million since 2009.

Back in September 2024, Gov. Kathy Hochul designated yet another $10 million to combat food apartheid, particularly in Staten Island where the FRESH program had only managed to open one store as of 2021.

Other communities across the country have implemented similar policies with even less success. In 2022, an independent grocery chain serving the Pine Ridge Reserve in South Dakota attracted the attention of the Federal Trade Commission when its owner, RF Buche, testified to the challenges of managing a store in a rural area. Challenges that mainly included prohibitive wholesale prices and delivery costs, which Buche wanted to see the FTC investigate. Memorably, former Chicago Mayor Rahm Emmanuel spent millions in 2016 to persuade Whole Foods to come to a neighborhood in Englewood on the South Side of Chicago, a community impacted by food apartheid, only for it to close 6 years later. Current Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson has expressed interest in a city-owned grocery chain, with a similar proposal to Mamdani’s, though his team opted not to apply for a key source of funding back in December, which suggests the program is stalled for now.

So if the problem can’t be solved by simply opening new stores in underserved areas, what are we missing? Are these communities just chronically lacking the purchasing power to sustain supermarkets?

Anti-corporate power policy advocate Stacy Mitchell thinks not. In an article for The Atlantic back in December, she argued that food apartheid “is not an inevitable consequence of poverty or low population density,” but rather is a relatively recent phenomenon, and one not necessarily solved by just opening more grocery stores, whether city-owned or not. Classism, inequality and racism are, of course, not new to American life, and are in fact part of its organizing principles — but despite this, Black, Brown, Indigenous, immigrant, poor, rural communities actually used to have grocery stores, several, even. So what happened?

In her piece, Mitchell traces the history of the American grocery industry, beginning with the Robinson-Patman Act in 1936, which took aim at then-dominant grocery chain, A&P. A&P used its “sheer size” to bully its wholesale suppliers into giving them lower prices, successfully undercutting its competitors, usually independent retailers. The Robinson-Patman Act made this illegal, banning preferential deals between wholesalers and their highest-volume customers. During the 40 years that the Robinson-Patman Act was enforced, locally-owned independent stores were able to compete with big businesses and thrive. They offered industry-leading innovations (including rewards programs and automatic doors) and served marginalized communities (even if imperfectly), alongside large publicly traded chains.

Then, as with so many policies that granted a modicum of ease and dignity to mid-20th century American life, Regan fucked it up. His government was convinced that antitrust enforcement was essentially a handout to small businesses, so along with many other common sense regulations on big business, his administration simply stopped enforcing the Robinson-Patman Act. Massive consolidation followed, eventually cannibalizing any semblance of competition from local independent retailers and empowering behemoth chains to abandon undesirable markets in favor of “efficiency.” This is part of the challenge for local legislators: once momentum for consolidation starts, it gets very complicated to unravel, even if municipalities try to fight back by coaxing retailers into their neighborhoods.

Therefore, Mitchell argues, until someone takes on this anti-competitive regime and decides to once again enforce the Robinson-Patman Act, the solution is not simply opening more grocery stores. Without doing so, fledgling ventures almost certainly won’t be able to compete with the margins available to big national chains, preventing meaningful competition. So, if the problem is with federal enforcement, this raises the question: Are city-owned grocery stores the most efficient means to address the problem of too-few affordable places to shop? Probably not, but they might be among the best solutions available to municipal leaders. Mamdani’s proposal mentions “partnering with local neighborhoods on products and sourcing,” which could help his administration build a competitive supply chain and avoid being undercut by bigger competitors. Ultimately, though, this is just a bandaid on an already infected wound.

At the end of her piece, Mitchell offers only a slight hope that President Trump could finally be the executive to take on the grocery giants. It would certainly be a slam dunk for him, especially given how much of his electorate seems to be motivated by frustration at grocery prices. But if the first weeks of his administration are to be believed, tackling an issue this straightforward and grounded, which would almost certainly improve the lives of millions of Americans, would be too boring and sensical to hold his interest.

what’s sustaining me:

READING:

For the next edition of TKB, I’m reading From Farm to Canal Street, by anthropologist Valerie Imbruce. Her most recent essay “From the Ground to Your Grocery Shelves” is available here.

For fiction, I’m slowly working my way through Parable of the Sower, by Octavia Butler, and my book club chose Emily Wilson’s translation of The Iliad (I loved) and Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo (haven’t started) for January and February, respectively.

For non-fiction, I read Mike Davis’ “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn” when the fires tore through LA back in January, and inspired by the events of this past week (attempted trade war, mass deportations, mass intimidation of asylum seekers), I’ve been slowly rereading the introduction to Harsha Walia’s Undoing Border Imperialism. With empathy and wisdom, Walia breaks down how terrorizing migrants and asylum seekers is core to the ongoing function of our political economy in North America, while the rest of the book imagines an alternate way forward. In a similar vein, I was very grateful to pour over Nora Loreto’s newsletter “What Canadian Nationalism?” — Nora is one of the few Canadian writers willing to offer an analysis on the nascent trade war deeper than just “Canada strong.” If you are looking for a principled, humane alternative to NYT’s The Daily, I recommend Nora’s The Daily News.

EATING:

My $5.83 grocery haul of 4 baby bok choy, a bunch of green onions, two large bags of pears (which became jam, see below) and a carton of fresh strawberries, from the criminally underrated Stiles Farmers’ Market in Midtown. I got sick a couple weeks back, so I’ve been subsisting on miso soup and toast with jam (and green curry from my neighborhood Thai place, tbh.)

MAKING:

Spicebush (aka Appalachian Allspice) Pear Ginger jam, inspired by forager extradinaire, Marie Viljoen, and condiment queen Claire Dinhut.

An adorable little “butter” sweater for my baby niece inspired by knitwear influencer, Elizabeth Anne Venter. Pics to come!