"one day the truck just didn't come:" how cuts to early-pandemic boosts are impacting mutual aid networks

also what to do if you encounter a person eating a messy bagel in public, and a hub for delivery cyclists opens on the UES

Welcome to the second edition of the Knife Bloc!

If you are new here, welcome! Here, you will find (if I’ve done my job right) principled coverage of the politics of food and sustenance in NYC. You will find stories about labor, mutual aid, urban growing, foraging, and the occasional goofy musing.

This week: what to do if you encounter a person eating a messy bagel in public (a parody of this popular Hell Gate piece), how local mutual aid networks and food pantries are strategizing to meet increased demand as the state continues to ignore the ongoing pandemic, and a roundup of food news and events in NYC.

But first:

A (Very) Brief Guide to Encountering a Person Eating an Overstuffed, Messy Bagel in NYC

Last fall, I came across Molly Osberg’s popular “A Brief Guide to Encountering a Weeping Person in Public in NYC,” subtitled, a “note on our responsibility to each other.” That got me thinking: what is our responsibility to each other when we perceive someone in the middle of the humiliating yet sublime ritual of a mid-afternoon bagel, devoured on the street, stuffed with an unholy, oozing 1/4 inch of cream cheese that inevitably ends up in an unsightly smear on their nose, stuck to their facial hair, or down the front of their black Patagonia puffer?

Do we politely avert our gaze? Offer a commiserating smile? Wipe the smeared spread from their face ourselves?

As Osberg writes of weeping, so too is it one of the “truest” pleasures we share as residents of this sinking improbable metropolis is enjoying an overstuffed pastry, unencumbered, next to a steaming pile of human excrement, or a bickering couple standing too close for comfort — yet not quite close enough that you can make out every word. It’s a ritual that demands respect, and, as with weeping in public, benefits from a “collective anonymity” that can only be found on the streets with 8.5 million people.

Generally speaking, in both cases, we are advised to uphold that sacred anonymity and move along. But, in extreme cases, we might be moved to offer to help.

Here, the advice is the same: You ask that person, with polite concision, if they would like a napkin.

And now, in a tooth-rattling tone shift, we turn to:

"One Day the Truck just Didn't Come.” How Cuts to Early-Pandemic Boosts are Impacting Mutual Aid Networks

Via Rauschenbusch Metro Ministries.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, mutual aid networks in New York City partnered with programs such as Pandemic Food Reserve Emergency Distribution (P-FRED) and Emergency Food Assistance Program (EFAP) to distribute fresh produce to their neighbors.

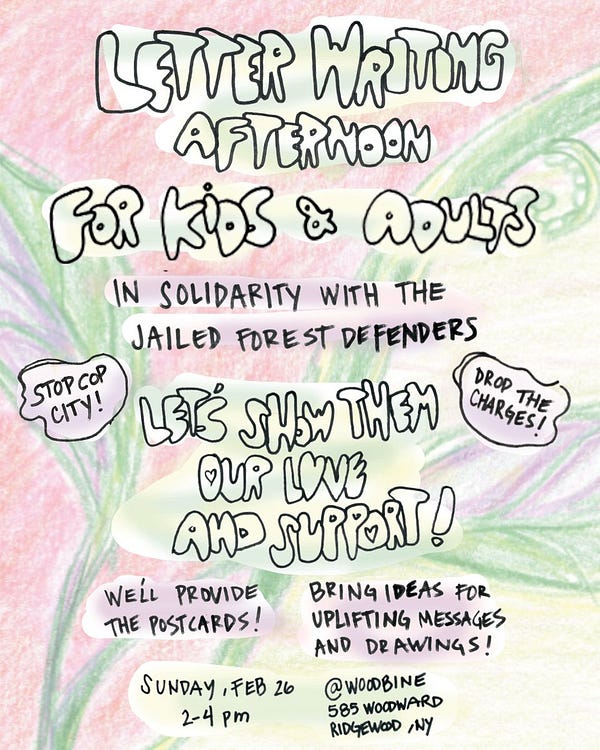

Just weeks into new mayor Eric Adams' term, however, local mutual aid networks began noticing disruptions to the programs they had come to rely on. Through P-FRED, grassroots mutual aid organizations, such as those at Woodbine social hub in Ridgewood, were able to order upwards of $1000 of fruits and vegetables to distribute at local food pantries.

“Then one day,” said Andrew Moore, a volunteer with Woobine, “the truck just didn’t come. We didn’t know why.”

In the following weeks, when they experienced trouble accessing the portal to order food and the amounts they could select dwindled, and other local organizations were experiencing the same, it was clear that the new administration had initiated dramatic cuts to the program.

These would not be the last Covid-era assistance programs in the chopping block. In March, the Biden administration will end emergency boosts to SNAP benefits, a $95 monthly increase per recipient which proved transformative for many. This comes after the Child Tax Credit expired at the end of 2021 the Emergency Rental Assistance Program stopped accepting applications in January 2023, both effective — though ultimately inadequate — experiments in mitigating poverty through social welfare during the height of the pandemic.

In the early days of the COVID-19 lockdowns, when the crisis felt dire and emergent for a majority of New Yorkers, organizers and activists hoped boosts to social services by the state and the proliferation of community-led mutual aid networks would result in a “new normal,” rooted in care, liberation and greater equality. The choice to end these programs, however, is no triumphant declaration the pandemic is over. Rather, ending these programs while millions of New Yorkers continue to rely on them signals a willingness to tolerate our current state of perpetual convergent crises as our new normal.

In response, mutual aid groups have been scrambling to fill the gaps once filled by the state’s emergency assistance.

Following cuts to New York’s fresh produce programs, Woodbine discussed scaling back, or even ending the food pantry, but instead committed to “doubling [their] efforts” to find alternative food sources to maintain the level of distribution their clients had come to rely on. Now they partner with a nearby Trader Joe’s, and most of what they distribute is non-perishable or about to expire.

At the time, Woodbine also urged community members to pressure local council members to oppose the cuts.

Council member Diana Ayala, who represents East Harlem and the South Bronx, and is the chair of the Chair of the General Welfare Committee, did so, fervently. In a hearing about cuts to EFAP, she said, “I just don’t see a world where we’re not going to have an additional need for resources, especially considering the high cost of fresh food.”

In response, Social Services Commissioner Gary Jenkins justified winding down these programs.“New Yorkers are rebounding and getting back to work and getting into the jobs that they so deserve,” he said. THE CITY reported that this claim was not supported by Department of Labor employment data. While pandemic lockdowns may have long ended, the economic need to which the food programs responded has certainly not.

P-FRED was always intended to be temporary, and was unlikely to be renewed at the start of the new fiscal year. But the program ended in April 2022, after unceremonious cuts in March, three months early, leaving grassroots organizations unprepared.

The ending of P-FRED was among the first of several cuts to early-pandemic era boosts to social services in the past year. The following September, in an effort to make up for budget shortfalls from the pandemic, Adams announced cuts to hundreds of vacant jobs at the Human Resources Administration (HRA), which is responsible for a number of programs intended to fight poverty in New York, including the Nutrition Assistance program, also known as food stamps. Council members Ayala and Jessica Gonázles-Rojas urged the mayor’s office to reconsider in a letter, citing that the HRA was already behind and only able to process 46.3% of applications for SNAP benefits.

Now, food insecure New Yorkers are again seeing diminished access to food assistance, this time as a result of cuts by the federal government. Beginning in March, the federal government will end the early-pandemic era SNAP “emergency allotment,” meaning that the 2.8 million New Yorkers who rely on nutrition assistance will see a $95 decrease in their monthly grocery budget. (Emergency allotments have already ended in some states.) Depending on their level of assistance, this could mean anywhere from a 27-50% cut.

The federal government is framing these cuts as “a return to normal levels” of nutrition assistance, as though “normal” is an achievable or even desirable state in the midst of a still-deadly pandemic. A return to pre-pandemic levels of assistance, which were never sufficient to the level of need, also fails to account for increases in food costs in recent years, due to supply chain disruptions and higher transportation costs, and corporate profits, among other factors.

Though folks on nutrition assistance use food pantries and community kitchens, Woodbine primarily serves people who are chronically food insecure and for whom SNAP is already inaccessible, according to the volunteer, Moore. As a result, he is unsure whether cuts to SNAP will have an immediate or dramatic impact on demand for resources from their pantry.

Ibrahim Ayo, who has been a beneficiary of support from Crown Heights Mutual Aid (CHMA) and DJs their regular block parties, feels that cuts to SNAP will definitely increase need in the community, particularly with the increased cost of food. “It means more stress on the helpers. More strain on the people that need help,” he said.

He also emphasized how difficult accessing SNAP is in the first place, particularly for folks who have been incarcerated or are in the shelter system. He told me about a man he is currently assisting who has just been released from prison. “I'm helping him learn how to use Zoom,” Ayo said. “He has no clue about the basics of joining a Zoom call. He’s not a dumb person, he just spent the last 30 years in jail.”

“One of the things we’ve been discussing [at CHMA] is how to go from just helping people with money and groceries to holistically helping people,” he said, so they aren’t as reliant on state-run programs that can be distributed sporadically, sometimes once a month, sometimes closer to every six weeks, or as is currently the case, reduced dramatically. He worries that the messaging around the cuts might not have reached people in time for them to prepare.

Aaron Moore (no relation to Woodbine’s Moore) is Food Justice Coordinator with Rauschenbusch Metro Ministries (RMM), which was founded in Hell’s Kitchen in the late 1880s and now partners with Food Bank for NYC. He told me that he has seen demand for food assistance climb back to early pandemic rates in recent months. This is likely a result of converging crises, such as inflation, rising food prices, and a lack of resources for arriving asylum-seekers. Thanks to a grant from the HRA, which, in part, they were able to win by citing their increase in clients during the previous year, it is a demand they are currently able to meet.

“The problem is next year,” said Moore. He doesn’t see the increased demand tapering anytime soon, but there is no guarantee extra funds will be available as individuals and institutions become increasingly committed to the notion that the pandemic is over.

Despite the state’s embrace of a bleak “new normal,” community-led mutual aid networks continue to distribute monetary donations and food. “We're just trying to see what resources we can get from ourselves and from the people around us and figure out how to share them in a way that can accommodate people when the state fails,” says Woodbine’s Moore.

Like Crown Heights Mutual Aid, Woodbine is committed to exploring holistic, autonomous solutions to community needs that more closely align with the possibilities envisioned during the early pandemic. They host Sunday dinners, film screenings and reading groups, and have antennas on their roof that provide wifi to the neighborhood. They even have a soccer team that plays in a local league.

Before the food pantry, though, they struggled to connect with their neighbors. “And now . . . we have a much bigger space and a lot more people operating there,” said Moore. “We all work together really well and that dynamic has really improved.” He adds, “It’s experimental, and we’re limited, but we’ve had some success.”

Read more:

NYC budget cuts could worsen food crisis for hungry families

Food pantries starved of deliveries following sudden supply cuts to City Hall program

As grocery prices climb, millions of New Yorkers brace for the end of pandemic-era food stamps

With SNAP supplements ending, City Harvest will offer food assistance

Enjoy a balanced [media] diet:

Listen to this “Bowery Boys” episode about the history of Fulton Fish Market from a couple weeks back.

Read this piece about the 5000 square-foot Upper East Side rest stop for delivery drivers — known as the “Brake Room” — recently opened and operated by, of all people/places/things(?), Chick-fil-A.

The Tasting Table did a round-up of the “12 Best things to Eat” at my old nemesis, Moynihan Train Hall. Read Hell Gate’s coverage of the space and its inexplicable lack of seating (and waste bins?) in what basically amounts to the journalistic equivalent of performance art.

This piece is not about food nor NYC, but it is excellent. Read “The Battle for the Soul of Buy Nothing.”

Also, I watched this video so now you have to too.

Events:

Visit the “Food in New York: Bigger than the Plate” exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, open through September 2023.

Rooftop farm Brooklyn Grange’s tours and workshops are always in-demand. Sadly this weekend’s “Introduction to Beekeeping” is sold out, but March 5th’s workshop, “Seed Starting and Propagation,” still has some space.

If you enjoyed reading about Woodbine social hub, consider stopping by their bake sale next Saturday to raise funds for their annual summer CSA.